El Grito and El Dia de la Independencia

Since I arrived on Sept. 5, vendors have been selling virtually anything you could imagine in the colors of the Mexican flag, to be used or worn on Independence Day, Sept. 16.

Also, decorations, which look awfully similar to me to those that went up for La Navidad, were hung.

Flags abound.

During the day of Sept. 15, as a build-up to El Grito, a re-enactment group rode their horses into El Centro for a short commemorative speech in the jardin. I was totally impressed with the condition of the animals; to a horse they looked well-fed and well taken care of. If the scenes here look like barely controlled chaos, then I’ve succeeded in capturing the essence of the event.

They were welcomed by the ever-present mariachi.

Some had their children with them. Some passed around a tequila bottle.

The speech.

They all wore these shirts saying that they’re playing the role of the conspirators (against the Spanish) from Querétaro, a near-by town.

And after the presentation, girlfriends and wives joined the riders as they galloped out of town.

Elsewhere in the jardin, the length of one entire city block was given over to vendors selling tchotchkes for the fiesta.

Groups of runners from various near-by towns made a symbolic lap around the jardin carrying “fuegos simbólicos,” torches similar to the Olympic flame…

…one, while checking his cell phone.

You have to love this hat!

Check out the electrician up on this structure, trying to get the lights to be red, green, and white.

A display in the gazebo in the jardin honoring Ignacio Allende, local revolutionary hero, after whom the town was re-named, from San Miguel el Grande.

The calm in the jardin before that evening’s “storm.”

I sat next to this charmer and her father, who was fine with me taking her photo, but she was having none of it. After about a half-hour of intermittent interaction, she did let me take it. She was so adorable, especially in her red, green, and white dress with matching hair ribbons.

The ceremony of “El Grito” (“the shout” — of Viva México!) commemorates that moment around 6 a.m. on Sept. 16, 1810, when Father Miguel Hidalgo exhorted people gathered for the morning mass at the parish church in Dolores (since re-named Dolores Hidalgo) to join the revolt against the Spanish government, which is considered the beginning of the Mexican War for Independence. Now, “el grito” is celebrated in every city in Mexico on the night of Sept. 15, here in SMA at 11 p.m. I was warned away from this celebration by at least three sanmiguelenses. I was told that more people than you could ever imagine jammed themselves into the relatively small jardin space and many were very drunk. Pickpockets were rampant. Think Times Square on New Year’s Eve on a smaller scale. Or Carnival in New Orleans. Fireworks rain down on the attendees, and one year, one of the elaborate structures, pictured below, built to deliver fireworks in place, fell over, although I noticed stout guys-wires on all of them this year.

I was told that sanmiguelenses stay home that night and the city is turned over to Mexican tourists. Basically, it’s a bacchanalia and they really trash the town. Many of the attendees are young adults, who act like they’re on spring break. It’s such a double-edged sword, because it’s great for the hotels, restaurants, shops and street merchants, but the tourists make so much noise long into the night, and make so much trash on the streets. The gringos do not act like this at all, and I hope the citizens of San Miguel have taken notice. I took the advice I’d been given and at close to 11 p.m., went up onto the condo’s communal terrace (where I met others, both a gringo and a Mexican family), and since I rent just around the corner from the jardin, I could clearly hear the historical el grito, traditionally delivered by the mayor, who, for the first time in SMA history, is a woman, and see the fireworks, which came from both the structures and also more traditional overhead displays.

On El Dia de la Independencia, I walked out of my apartment at 11 a.m. to try to find the promised parade (no route was given in the newspaper), and found that I was on it. Hundreds of people were lined up. (That’s the very attractive door to my condo development below.)

And that’s my bank, Monex, right next door, where I exchange dollars for pesos when needed.

The parade consisted primarily of the students of every school in San Miguel, each dressed in a different, distinctive uniform…

I really liked this man’s outfit as he walked with one school group.

…re-enactors, playing the part of local revolutionary heroes…

the local policia…

any number of reynas (queens) from various areas…

and representatives from other states in Mexico in their traditional garb.

This is not the bomb squad! Bomberos is fire fighters in English. This is their ambulancia.

And you always know when the parade is over, as the “limpias,” the cleaning crew, bring up the rear, in this case mostly to clean up horse droppings.

It rained hard for about two hours in the afternoon, dampening the festivities for sure, but cleared in time for a bull fight in the arena at 8 and another round of fireworks in the jardin. You can see how close I am to them, as this photo was taken from my balcony.

Celebration in honor of San Miguel Arcángel – Part I

Carlos, my Spanish teacher, thinks now that I am an “estudiante avanzada,” I should be learning some idioms. Well, my favorite so far is “echar una cana al aire” (literally, to throw a grey hair into the air). And it means (drum roll, please): to have a mistress! I don’t think I can beat that one in English. Let me know if you can think of any I can counter with. I’ve been racking my brains to think how I might use that phrase in everyday conversation. Another favorite, of the dozens and dozens that use the verb “echar” — to throw — is echarse un taco de ojo (literally, to throw a taco of the eye), and that means to observe an attractive person of the opposite sex.

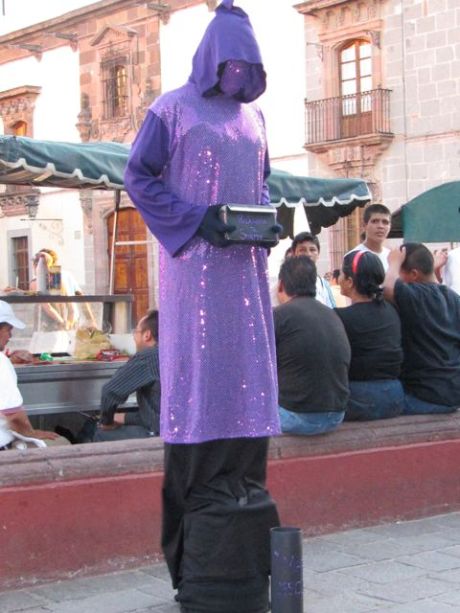

One evening before all of the Independence Day celebrations, I was hanging out in the jardin, when I spotted a street entertainer setting up, the likes of which I hadn’t seen before in SMA. He was tall to begin with, and then he stood on an over-turned bucket so he towered above everyone else. He had a tall, narrow tube for coins directly in front of him, probably so nobody could dip in and help him or herself.

I think the guy below might have been a shill, as he immediately came over and deposited a coin, which set the entertainer into motion. With Michael Jackson-esque robotic movements, he first shook hands with the donor and then opened the box he was holding, offering tiny little scrolls of paper, which turned out to be like the fortunes in a fortune cookie.

This girl seemed a bit reluctant to extend her hand.

The guy was cleaning up! Of course every kid wanted to give him a coin. I certainly did, since he provided me with quite a bit of entertainment and allowed me to photograph him extensively.

I have joined an English hand bells choir which meets weekly on Friday mornings. I wanted to try something totally new, and because I can read music, I possessed the only requirement to be a member. Our group has been invited to perform the “special music” at the UU service the last Sun. of the month. I’m already nervous! (There’s one other member who did not want to be photographed.) Our teacher is Liz, the woman on the left in the blue blouse. The cat does not play.

The man below is selling potting soil door-to-door and shop-to-shop from his burro’s back, and insisted on a coin when I started to take their photo.

There’s a store in the Cherry Hill Mall in New Jersey called Forever 21. Here’s the SMA version for an older crowd:

Even though Halloween is not celebrated in Mexico, they do get into the pumpkin theme. The dog is real and presumably not for sale. As you can see, it’s a very pet-friendly place.

T.S. Eliot may have thought that April was the cruelest month, but let me tell you that September is hands down the noisiest month in SMA! Oy! The final fiesta of the month — and, my maid assures me, for quite a long time, gracias a Dios — is the celebration of the birthday of San Miguel Arcángel, the patron saint of SMA. Festivities got started early Friday evening with the usual four-ring circus in the jardin.

First up was a drum and bugle corps of school children.

As they left, this colorfully outfitted group first made sure that all of their ropes were in proper order. Then they danced around their pole to the music of a tiny drum and flute, both played by the same man.

One by one, some of the men climbed to a tiny platform at the top of the pole and spent quite a long time creating harnesses for themselves out of the stout ropes, while a couple of others remained below to keep the pole steady.

When they were all sure of their harnesses, down they came, unraveling around their pole like a Maypole dance in reverse. Pretty impressive, let me tell you.

The crowd was rapt!

And while that was going on, another ring was occupied by what looked to me to be Whirling Dervishes in beautifully embellished costumes. They did a sort of twist dance, and I haven’t a clue what they are or where they came from. Although they wore men’s masks, there were women among the dancers.

And then — right in between these other groups — were the Indian dancers, whom I’ve seen several times before at other fiestas. Because of that, I resisted the urge to photograph them all over again, except for one amazingly tall (by Mexican standards), handsome specimen I couldn’t take my eyes off. And I wasn’t the only one. After the dancing stopped, many female tourists asked to have their photo taken with him, to which he graciously agreed.

Off to the side there was what seemed to be an alternative Indian dancing group, mostly teenagers, and some looking mighty threatening in their animal skins and fierce face paint.

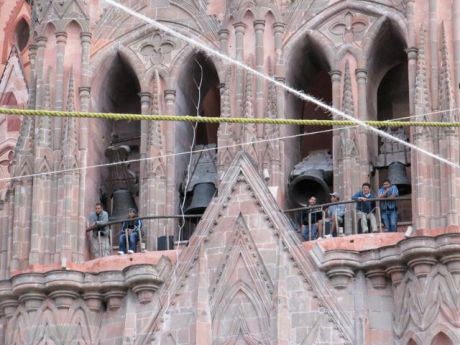

And to add to the cacophony, the bells in the parroquia were being run almost constantly — by hand by men right next to them! I hope they hire deaf people, because if they weren’t deaf when they went up there to work, surely they are by the time they come down. They just keep flipping them over and over. It must take some real brute strength until they get them going.

When it was completely dark, a small religious parade came through, bringing what I assume was an icon of San Miguel Arcángel.

And finally — devils! Don’t ask, because I haven’t a clue.

And this was only the night before the celebration!

Celebration in honor of San Miguel Arcángel – Part II

Every Saturday, there is a Tianguis Orgánico in a lot owned by the new, ultra-luxurious Rosewood Hotel. It used to take place in Parque Juarez, and when I attended this year in the new location, I was blown away by the size to which it had grown. I had no idea that there were so many people growing food organically around here. There are also lots of beauty and health products, baked goods, clothing, jewelry, food to eat right there, and more. It’s also a very social time. I’ve attended every Sat. I’ve been here, and I always meet people I know. I submitted the photo below to Atención for their Only in Mexico section. I’ll let you know how it fares.

Later that Sat. afternoon, I was shopping at the big fruit and veggie market for grapes (which I did not find at the organic market) to take to church for fellowship hour nibbling, and came upon a little (not organic) market in the street.

Those are giant already-cooked sweet potatoes on the blue box behind the roasted peanuts.

I marveled at this scene. Where in the world were they getting their Internet signal from?

I thought this looked particularly awful. Why would you want bread that looked like watermelon?

I think I’ll submit this one below to Atención also. Those little plastic things with the palm trees are homes for the turtles.

The festivities for the actual birthday of San Miguel Arcángel had begun much earlier that day at the ungodly hour of 3 a.m. in a ceremony called La Alborada (the dawn, but it was waaaay before dawn), which included processions starting at different points, but meeting up in front of the parroquia at four. The celebration combines Christian and pagan symbols and rites. When the processions meet, those walking and those waiting for them sing las mañanitas (happy birthday) to the patron saint, fire crackers go off (called “the burning of the powder”) and church bells ring. Trust me when I tell you that not a single person in SMA was sleeping after 4 a.m. that day. That evening around 5 p.m., a huge parade for San Miguel Arcángel began. People came from all over the region with individual offerings to the saint, but the main reason for the parade is the bringing in of huge floral offerings called xúchiles. They are constructed of cucharilla (green desert spoon, which is nearing extinction because of indiscriminate use), giant reeds, and marigolds.

This is one of the xúchiles. Look how large it is and how many men are needed to carry it.

They are then stood upright around the entrance to the parroquia.

Look at this magnificent thing! Can you imagine how many marigolds are in it and how many hands and hours it took to fashion it?

The next two photos show off some very interesting hats. The ones immediately below are made from feathers.

And these went by so fast, I couldn’t tell what they were made of.

No display or parade in SMA is complete without a devil.

The marchers all came up Calle Canal and hung a right to proceed to the parroquia. They just kept coming and coming and coming, for over two hours. I kept wondering where they were all going to sleep and eat and go the bathroom.

The bell ringers had the best view in town!

The parade ended with the arrival of the mojigangas, the giant dancers. After it became dark, fireworks were shot off (endlessly). Here they like their celebrations long, loud, and colorful.

Ojalá Niños Art Walk

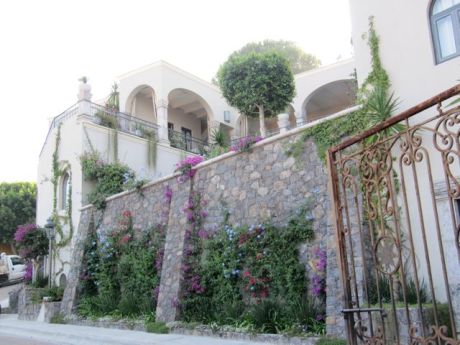

Thought you might be interested in seeing how the other 1% lives in San Miguel. (We used to call it the “other half,” but now we’re down to 1%.) I took these photos on the long, totally up-hill walk to the home of the woman who teaches the English hand bell class.

On a Sunday, two weeks ago now, I offered to help out Ojalá Niños with their second annual fund-raising art walk. The art walk is a favorite activity here in SMA, usually confined to El Centro. You publicize your event, display your art at your gallery, have refreshments and drinks at the ready, and await the folks, and it worked just that way for Ojalá Niños, except that this art program for children in Viejo San Miguel is not in El Centro, but way out a dirt road in the country, and it rained — hard — on Saturday, making the only access road impassable. A call went out for an emergency truckload of soil and many willing workers made the road as good as new. Until it rained again in the wee small hours of Sunday. More soil, more workers, but the road was ready when we arrived. In fact, we were the first car to roll over the repaired section at about 11 a.m. — and the art walk was called for noon to 4 p.m. Whew!

This area displayed the artwork done by the youngest groups. You can see that some soil was needed at this location, too, to prevent people from getting mud on their shoes from the rain.

And then we were open for business. All afternoon, I worked at one of two cashier stations, got to sit down the whole time, and was in the shade, chatting with interesting people. This is work?

This magnificent mosaic mural was done by the oldest group of kids, and has the famous quote, “Be the change you wish to see in your life,” from Gandhi. This and other murals they’ve done at Ojalá Niños have gotten them much attention and potential business. A woman who taught groups in Guatemala about the cooperative model is going to come to the program to help them start one up. These kids could soon be contributing to their families’ income and perhaps even finding their way to a lucrative profession in their adulthood — all because of the volunteers who teach skills such as this one at Ojalá Niños. Of course that was not the original intention of the program — rather giving kids from very poor families a chance to express their innate creativity — but, hey, if you can turn your art talent into income, that’s all to the good.

These cactus masks were not for sale, but got so much attention, that you can bet they will be next year and in far greater abundance.

Below you can see another example of the fine mosaic work the kids have done, in addition to lots of other work. Perhaps because the weather was still a little overcast, suns were selling like hotcakes!

A wood-working class produced these brilliantly-colored bird houses and natural-wood trucks.

Fewer people attended the art walk this year, I was told, perhaps out of fear of what the road would be like after the rain, but those who did come bought generously. The gross proceeds were 17,000 pesos or $1332 USD. After subtracting costs of publicity, drinks and snacks, and the roadwork, the profit was 8759 pesos or $680 USD. It didn’t seem like a lot to me for all of the work that I know went into the art walk, and we surely hadn’t counted on the expenses of the road repair, but I also know that money goes a whole lot farther here than it does in the US. Everyone seemed pleased.

Here’s a photo I took near my house that I just love. The flag and papel picado were still up from El Dia de la Independencia several weeks prior.

Cervantino – Part I

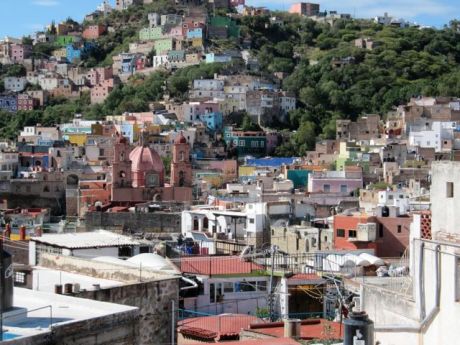

Way last February, I met a woman, Enaid, at the SMA Writers’ Conference, who lived in Guanajuato (Gto), the capital city of the state with the same name (SMA is in this state, also). She had come to Gto from Chicago via Costa Rica. I had been thinking of going to Gto this fall for Cervantino, the International Cervantes Festival, now in its 39th year — a smorgasbord of the performing arts over about a three-week period — and when I expressed interest in renting her casita, she pooh-poohed that and invited me to be her house guest instead. We agreed on a week and before I even got there, she provided me with incredible services: walking me through the complicated schedule by phone and e-mail, helping me to zero in on the programs I wanted to experience, then stood in lines to purchase my tickets. Wow! That’s hospitality. Early on a Tuesday morning in the middle of Oct., I boarded a bus for the slightly more than one hour trip to the state’s capital. Then, following the careful instructions Enaid had given me, I guided the cab driver to her house. And what a house it is! I learned that it was only a year old, and that in the year before that, Enaid had moved to the city, rented an apartment, found a building lot, hired an architect (although she already had the whole place planned in her mind), and had her house built — all in a foreign land and in a foreign tongue.

Like many parts of Gto, Enaid’s house is way, way up on a hill. This photo is taken from the top of the hill on which her house sits. She put in the driveway and stairs. Except for when I arrived and departed by taxi, we walked up and down that hill (and many others in town!) several times every day.

It’s hard to see in the bright sunlight in which I took this photo that the house is a lovely shade of violet.

And that color scheme is continued inside. Actually, Enaid had a magnificent silk scarf framed and hanging on the wall from which she took her color palette.

There’s the scarf! And she has a tasteful array of art pieces that she has collected from her trips around the world.

This was my bedroom, which was created by pulling the queen-sized bed out of the wall! And what’s on the other side of the wall where the bed usually stays? A platform over its “garage” on which Enaid’s exercycle resides with a killer view. When this room is not being used for guests, it is Enaid’s computer room.

The kitchen picks up another of the dominant colors in the scarf. The master bedroom and bath take up the second floor.

After a sumptuous brunch, Enaid led me on an orientation tour of the city. There is excellent and cheap bus service and of course taxis for really out-of-the-way venues where a few of our programs took place. I was surprised to see these burros on Enaid’s street, as the capital is much more sophisticated than SMA.

Gto is situated in a narrow valley with narrow and winding streets, called callejones (alleys). Cars can’t pass through many of them. Constant flooding from water pouring down the hills led to the construction of large ditches and tunnels to contain and divert overflows during the rainy season. In the 1960s, a damn was constructed which controlled the flooding and the tunnels were converted into a warren of underground roadways.

Cervantino had its birth when college students presented readings of Cervantes’ work in the streets. Now, each year, Cervantino honors a number of countries by inviting them to send performers; it also features a different Mexican state each year. To my delight, the guest countries this year were Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden. I mean, what are the chances, with my son and his family living in Finland, that this would be so? And Nayarit was the featured Mexican state.

The theme this year was “Los Dones de la Naturaleza,” The Gifts of Nature. I was just crazy about this logo, a depiction of Cervantes created from leaves.

This is the famous Teatro Juarez, to which I had paid a brief visit on a day trip to Gto some years back. Constructed between 1872 and 1903, it is the only theater in the country to have maintained the original furnishings. More on this a bit later.

I snapped this photo to show the juxtaposition of one of the old churches with a modern sculpture.

This was something completely different! It first appeared at the botanical garden in SMA before making the trip to Gto for Cervantino. Fitting in completely with the theme of “The Gifts of Nature,” the Mexican founder of the Laboratory into Resonance and the Expression of Nature has managed to make plants sing. The article in Atención said that electrodes were connected between a cactus’ root network and a specially-constructed type of lute whose core is formed by strings and precious woods that vibrate when they receive signals from living beings. This produces resonance within the instrument’s mechanisms, generating unique and unrepeatable music. The lute translates the vital signals of the cacti into sounds. Now I don’t pretend to understand any of that, and I didn’t see any electrodes at this exhibit, but the lute was indeed playing other-worldly sounds that drew much attention.

This is the University of Gto, obviously a school of higher learning.

We went to a display/sale of Mexican folk art assembled especially for Cervantino.

This was my favorite. I fell hard for this paper piece, which was selling for the ridiculous price of the peso equivalent of $50 USD. I was especially taken by the corrugated cardboard box bent to fit the mask perfectly.

Then we went to a special exhibit of handcrafts from Nayarit, the festival’s featured Mexican state, and came upon this teenager beginning to cover a piano in the tiniest beads you’ve ever seen — one by one.

The day before I left — a week later — I made it a point to return to see the progress on the piano. We saw a picture in a magazine there that showed a finished product, and even the keys were beaded!

Right across from this church was the bus stop to take us back into Enaid’s neighborhood, so I got to look at it up close quite often. The green area in the foreground is Plaza de la Paz, where I lost my fleece jacket. The cast-iron benches are the most uncomfortable things I’ve ever sat on (and they are identical to the ones in SMA’s jardin), so while waiting for Enaid to go to the bank, I folded my fleece and sat on it. When she came back, I just stood up to join her, forgetting all about the fleece. Of course it was gone by the time I remembered it and came back. Sigh.

My first performance was the Inauguration on Wed. night at la Alhóndiga. (The first battle in the Mexican War of Independence was fought at La Alhóndiga de Granaditas [public granary] between the insurgents and the loyalist troops.) The group performing was Orquesta de Jazz de Estocolmo, from Sweden. I expected that there would be long-winded speeches, in Spanish of course, before the music began, it being opening night, but at precisely 8 p.m. the music began, to my delight. I was surprised to see that in an orchestra of close to 20 people, there was only one woman.

The second night, also at la Alhóndiga, turned out to be my favorite performance of the week. It was the Ballet Folklorico de México. I’d seen this group in la Ciudad de México over 50 years ago, and several times at the Academy of Music in Philadelphia in the intervening years, and was surprised to see that the dances had not changed. The costumes were brilliant, the music lively — and loud — and the energy and joy projected by the performers was catching.

La Alhóndiga is an outside performance space. I was extremely impressed to learn that all of the seats behind the fence in this photo below are free. It’s first come, first served, and people start lining up hours before curtain time. Directly in front of the fence is general seating, where you can sit wherever, and then, closest to the stage is assigned seating at a slightly higher price, of course. None of the performances was expensive at all, though. The six tickets for evening performances that Enaid bought for me cost a total of $68 USD. Another interesting custom is that there are three calls, starting about 10 minutes before the show starts. A recorded voice says, “Primera llamada, primera llamada,” and people who are milling around start to take their seats. Then there is a “Segunda llamada,” and just moments before the curtain opens, “Tercera llamada.” At this point, any unclaimed assigned seats are fair game, and people sitting in general seating (not in the free seats, however) or even in less-desirable assigned seats are free to move into them. If you’re holding an assigned seat for a friend with a ticket for it, you cannot hold it past tercera llamada. If they come late, they cannot insist on having their seat.

Because this is an outdoor venue, lots of people just stood on a bridge next to it and watched, and a private home across the street put up folding chairs in their third story enclosed porch and filled them up for every performance. It was quite chilly in the evenings, and I was glad that Enaid warned me to bring warm clothes.

Cervantino – Part II

First, I must report on three interesting and/or funny T-shirts I’ve seen on Mexicans here recently. I’m sure they have no idea what they say; they probably bought them at a flea market or at the Tuesday Market from a pile of used clothing.:

1. Not now; I’m tanning!

2. I (heart) soccer moms (this on a teen-aged boy).

3. No, I won’t fix your computer for you (also on a teen-aged boy). Maybe he did know what it said…Since the majority of the Cervantino presentations that Enaid and I chose to experience were in the evening, we had the daytimes free to explore. One day Enaid hosted her bridge group, and since I don’t play bridge, I was off on my own. I went to a number of museums that had special exhibits, all under the auspices of the university and all within a few steps of each other. I saw Danza de Pájaros (Dance of the Birds), paintings and sculptures of birds and other elements of nature, in keeping with the Cervantino theme, by Nayarit artist Vladamir Cora. I absolutely loved this exhibit. If they had been for sale, and if I had the kind of money needed to buy them, I would have bought a set of four paintings of birds that just knocked me out. A photographic exhibit right next door didn’t thrill me at all; it was photos taken by iPhones that were supposed to represent some social statement. Then I slipped into an extremely unusual display called To Feel Well: An exposition of sexual and reproductive rights, which included photos, video, and installations, a product of the collaboration of the Embassy of Sweden in Mexico and the University of Guanajuato. The promo material said that in Sweden there exists a long tradition of sexual education that seeks to combat myths and prejudices to guarantee that all have the right to three fundamental liberties: to exist, to choose, and to enjoy. This exposition guided the attendees through the world of sex. You were able to see the movie “Por el mundo del sexo” and to read near-by the most commonly-asked questions about sexuality and health, with answers.

I’m sure in my lifetime I will never see the screening of this movie or an exhibition like this one in any museum or school in the U.S. It was incredibly frank, open, honest, and direct. Every single possible combination of people and/or positions was shown (as you can see in the background on the poster below). How to put on a condom was demonstrated on a wooden model. The all-teenage audience was rapt. Hoorah for Sweden, and I was thrilled — although surprised — to see that Mexico, well, the capital city of the state of Guanajuato and its university anyway, was this forward-looking. Below is the poster advertising the exposition.

The final exhibit I saw, at the Museum of Natural History, part of the collection of Alfredo Dugés (France, 1826-1910), wasn’t so thrilling, except for a specimen of a two-headed calf. The lighting was kept purposefully low, which made it hard to see some of the smaller and darker specimens and to read the accompanying notes, which were in Spanish anyhow.

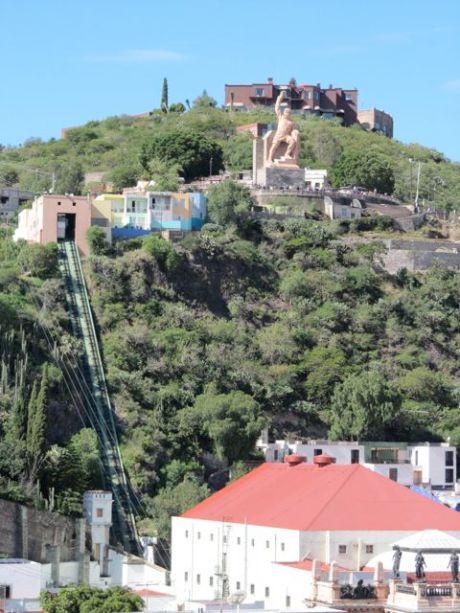

I walked around a bit, taking photos. The giant statue at the top of this photo is the famous Pípila. Pípila means hen turkey in Spanish and Juan José de los Reyes Martínez Amaro (1782-1863) had some mental and physical defects which caused him to walk like a hen turkey, thus the nickname. He was an object of ridicule. As a young man, he worked as a miner and had come to Gto from San Miguel. He became famous for an act of heroism near the beginning of the Mexican War of Independence, on Sept. 28, 1810. The insurrection had moved from Dolores Hidalgo to Gto. The Spanish barricaded themselves — along with plenty of silver and other riches — in a grain warehouse known as La Alhóndiga de Granaditas. It was a stone fortress, but with a wooden door. With a long, flat stone tied to his back to protect himself from the muskets of the Spanish troops, Pípila carried tar and a torch to the door of the Alhóndiga and set it on fire. The insurgents — who far outnumbered the Spanish inside — stormed in and killed all of the soldiers and the civil Spanish refugees. I knew the story of the door burning, but I was glad to learn what the nickname Pípila meant. When I had visited Gto on a day trip some years ago, I was up on that platform at the base of the statue to overlook the city. I decided not to take the funicular up to see it again.

A view of the very colorful city from the terrace of an artist friend of Enaid’s, who invited us for coffee and to see her work.

We walked on this typical callejon (alley), on the way back from her house.

Of course we had a lot of wonderful meals out. The photos below were taken at a restaurant called Las Mercedes, which is in a private home. Mercedes is the chef and her husband handles the front of the house. It’s way, way up one of the many hills that make up the city, and in addition to a super meal, we experienced a beautiful sunset. Enaid’s looking pretty spiffy and I, a little done in. (It was also a bad hair day, as were most of them while I was in Gto, since I got a pretty bad haircut right before going there.) Both of us had fish dishes.

Another place we ate had the odd name of Antiguo Vapor (Old Steam). Turns out the restaurant was the city’s original bakery and we were shown the oven that was used.

One evening, we went to this fairly new venue outside of the center of town, the Auditorio del Estado (the State Auditorium) to see a modern dance program called “Now She Knows,” presented by the Zero Visibility Corp. from Norway. Others liked it pretty well; I, not so much. The auditorium, however, was splendid, and quite a change from the Alhóndiga, the outside venue we’d been seeing most programs in.

While attending programs, I had two adventures that are worth reporting. On Saturday morning, I decided that I wanted to go hear Magos Herrera, an extremely well-known Spanish blues singer who has earned many awards, performing in the ex-hacienda de San Gabriel al Barrera. This was not a performance for which I had a ticket, as my decision to go was somewhat last-minute. I took a cab to the out-of-the-way place and when I got there was told that it was completely sold out. My heart sank. I didn’t know how I was going to get back home. One of the ushers saw my disappointment and told me to go speak to a bunch of other ushers closer to the entrance. I told them my problem and that I’d been sent to them for help. They told me to stand on the side for a minute. After about five minutes, one said, “Pasale, señora,” and gestured that I was to go in. I said, “Sin entrada?” “Si, si, pasale.” I have no idea how I got in or why, but I was thrilled. I found a seat next to a very young couple from Colorado and we had a good chat before the concert began. In between two of the numbers, the woman said she heard their baby crying. The baby was being cared for by his parents, who lived in Guanajuato. They were playing with him on the immense grounds of the ex-hacienda. So they left. Magos had the most gorgeous dress on. You can’t really appreciate it here, but everything black is embroidered. It was strapless and because the stage was in the shade, she needed that sweater wrap. The skirt came up in the front to about knee length and she had on beautiful white silk pants and cool shoes. The back of the skirt was quite full and long, and she had to pick it up to move around the stage. She and her amazing four-man band were a hit! She performed in SMA the next day.

The other adventure took place during attendance at the last performance on my list, by the Orchester Wiener Akademie, from Austria, playing La Viena Clásica: Haydn, Mozart, y Schubert in Teatro Juarez. They were stupendous. The seats were not. You’ll remember that this theater is the only one in Mexico that has all of the original furnishings. My seat was on a bench without a back in a small box in the third balcony which I shared with three other people. Behind us was another bench, also seating four people. Big, powerful lights were directly in front of us. Gracias a Dios, they were not being used for this performance or the heat would have been incredible. There was so little leg and foot room between the bench and the wrought iron guard rail that I couldn’t put my feet down flat on the floor. Those Mexicans over 100 years ago, I guess, were a whole lot shorter and with smaller feet than mine. I don’t know how the taller, bigger man next to me managed. My back was killing me, and during intermission I told an usher that I had to have another seat, one with a back on it. Since the theater was only about two-thirds full, that was not a problem. She showed me to another box, further around the curve from the center, where there was a vacant chair, and I shared that box with two other women. But, being in the back row, I couldn’t see the orchestra (the women in the front row had to lean way out over the railing to see); I could only hear them. Luckily, they were very, very good, so it wasn’t too bad. The place where Enaid showed me to wait for a cab afterwards happened to be at the stage door, and as the orchestra members filed out to a waiting bus, nearly to a person they lit up cigarettes! I was horrified!

On Sunday morning, we went to a freebie circus show in Plaza San Fernando, called Un orteil dans la vide, consisting of “three colorful and eccentric women (from Quebec, Canada, thus the French title) in the midst of a huge German wheel. Here they play, dive, dance, and do acrobatics, creating a whirlwind of stunts and, of course, jokes.” One woman played the accordian. They were lots of fun, and they also appeared in SMA.

We did a little souvenir shopping in the Mercado Hidalgo, sort of like the Reading Terminal Market in Philadelphia. Sort of. I bought a great Cervantino T-shirt which I use for my yoga practice.

And no visit to Gto would be complete without a peek at the Callejon del Beso, featuring two houses facing each other on the narrowest of all the streets that make up the city, so narrow, in fact, that the occupants can kiss each other from their terraces.

Although I had a wonderful time in Gto, and enjoyed Enaid’s super hospitality, I was very happy to be back in SMA. Going from there to the capital city was somewhat like going from Philly to NYC.

Other years, there has been a smattering of Cervantino events in SMA, but this year, there were many, necessitating a full-color brochure of offerings. I did manage to get to some of them after I got back. I’m hoping that this new companionship between the two cities — only an hour away from each other — will continue into the future for Cervantino programs.

Run-Up to El Dia de los Muertos

When I returned from Guanajuato, I discovered that a tent city had been erected in the Plaza Civica in my absence. I didn’t know what the booths were selling or why they needed to be so protected. Then, when I got closer, I saw that they were offering some of the elements needed to erect altars to the deceased for Dia de los Muertos, Day of the Dead, and held two things that could not stand up under the daily onslaught of the sun: things made out of sugar and candles. I’m sure most of you know that Dia de los Muertos is not a morbid, sad occasion, but a joyous — even raucous — celebration of the lives of those who have gone before us. Families erect sometimes simple, sometimes elaborate altars to remember the deceased. In many of the following photos, you will see more marigolds than you’ve ever seen in one place before. I was told that the scent of marigolds can bring the spirits of the dead back. Indeed, in the jardin, with so many altars awash in marigolds, their unique odor permeated the air.

On the altars, in addition to marigolds, are typically hygiene products, such as soap and cologne, so that the visiting spirits can clean up before the fiesta begins. Tiny recreations in sugar of their favorite foods are frequently a part of the altars. There are sometimes cans of Coke or beer or bottles of tequila so that the spirits will have a good time at the party. And usually you will see a photo of the deceased. I am just enchanted by these miniature creations.

Candles, of course, for the continuation of the parties into the evening.

If this doesn’t look exactly like an enchilada in mole sauce with rice on the side, I don’t know what does. And there are fried eggs with perhaps fried potatoes and a chili, of course. All made out of sugar.

Another favorite meal, although I’m not sure what it is.

These were a favorite of mine.

At the organic market on the Saturday before the holiday, lots of stalls were selling items like this pan de muerto tradicional (the sugar-coated one at the top of the basket). They come in smaller, individual versions, too. Have you ever seen a friendlier face?

Of course a Catrina mojiganga making the rounds is a must.

I believe I told you earlier that I had joined an English hand bell choir. We were invited to perform at my UU church last Sunday. Only the leader and I are members of that congregation. The others belong to Community Church, a new, non-denominational Christian church in town. I’ve been playing for exactly two months, but others longer, perhaps six months, and our leader, 30 years. Just a week before our performance, one of our members slipped in the shower and seriously broke her ankle. She had an operation on it, but she and her husband decided to go home early as she was having difficulty with the crutches and her husband was somewhat older and a bit incapacitated. (It was at this point that I asked my landlady to have grab bars installed in my tub/shower, and she immediately did.) Our leader took over the bells of the “fallen woman.” We did some heavy rehearsing as the date neared, and I think we did pretty darned well. Of course I couldn’t actually hear how we sounded as I was so focused on playing my part correctly. Unfortunately, I had to give notice that I wouldn’t be continuing after the performance. I came to Mexico with a pain in my elbow and was pretty sure that the ringing of the bells — which is a scooping motion with a upward wrist flick at the end — would not be good for my elbow, and was I right! At this point I have pain while wringing out a washcloth with two hands, and I can’t pick up either a glass or a book with my left hand; it’s just too weak. So, while the bells certainly didn’t cause my problem — it may be arthritis — it did aggravate the situation. I’m really sorry, as I enjoyed learning a new skill and the comaraderie of the other women. I brought my camera to church and was going to ask someone to take our picture while we played, but I thought better of it. No sense in adding any distracting element.

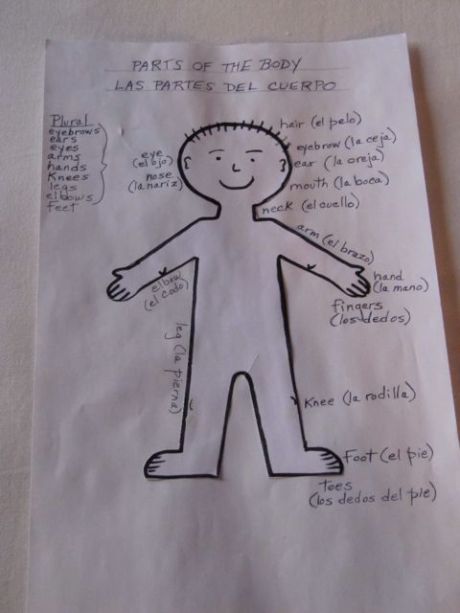

I bought a printer the first week I was here, and I’m making great use of it for the ESL lessons for Mercedes’ kids that I give every week. Last week, I printed out paper dolls (at 140%) on card stock and clothes for both sexes (at 90% — that was a lot of fun figuring that out) on regular paper. I cut the items of clothing out and glued them on sheets, then took the sheets to be copied. The idea was to learn the names of the clothes in English. Their homework was to color in the clothes and the bodies, cut them out, and write the names of the articles of clothing on the back. I gave each of them a small manila envelope to keep the dolls and their clothes in. I’m eager to see what they come up with. Then I used the same size doll to help them learn parts of the body in English. We did a lesson on plurals, too, and found that only one — feet — was irregular. Here’s what some of the papers looked like.

In the middle of the run-up to El Dia de los Muertos, race cars in the Carrera Panamericana (Pan-American Race), the most famous rally in the world, came through town, making a short stop in front of the parroquia to receive a bottle of water, a medal on a ribbon and a packet of materials, and then stopping for a meal and to service their cars on a street on the outskirts of town. “The Panamericana was run for the first time from 1950-54, when the Mexican government inaugurated the Carretera Panamericana (Pan-American Highway), which runs through Mexico from Guatemala to the U.S. In 1988 the Panamericana was reborn as a rally by a group of car enthusiasts headed by Eduardo Leon, current honorary president of the event. Since that year, the race has begun in Chiapas or Oaxaca and ends in Nuevo Laredo; however, this year it will end in Zacatecas due to the problems along the border. The rally lasts seven days and the cars run 4,000 kilometers through cities such as Oaxaca, Puebla, Querétaro, Morelia, SMA, Aguascalientes, and Zacatecas.” (Atención) What I didn’t know until they appeared was that this is an event for antique cars. There are drivers from Sweden, Switzerland, Germany, Finland and Mexico. Last year’s first-place winner was from Finland and second place from Mexico, with a difference of only 20-30 seconds!

This was the first car to arrive.

One funny thing I saw was an Oldsmobile with this saying on the back in Spanish, “Olds in Name Only!”

One of the things that makes me love San Miguel de Allende so is that I have many peak experiences here. A recent one was to have met the most extraordinary, unusual, and interesting man ever in my life. I attended a documentary called “El Pianista de la Sierra Madre,” and the subject, Romayne Wheeler, was there for a Q&A afterwards. He was incredibly warm, open-hearted, and deeply spiritual. His unique story is this, in a nutshell: He was born in California in 1942, and studied piano as a child. When he was eight or nine years old, he was traveling with his father to Puerto Rico for a piano competition. He heard Andrés Segovia play “Recuerdos de la Alhambra,” by Francisco Tarrega, on his guitar, and at that moment Romayne decided to dedicate his life to music. As an older teen, he went to Austria (he loves the mountains) and studied for 12 years, graduating with a degree in performance and one in composition. His professors suggested that he record the music of the indigenous people of his own country before it disappeared forever. After spending numerous years on that project, he decided to travel to Mexico to study the role of music in the spiritual lives of the Tarahumara Indians, who live in caves in the Copper Canyon. (I saw the Tarahumara and visited one family in their cave when I traveled to that region some years ago with Elderhostel.) He was enchanted by the Sierra Madre and the gentle Tarahumara character. He returned annually, bringing a prototype of a solar piano with him.

Eventually, Wheeler and the Tarahumara bonded, and he decided to settle permanently among his adopted family where he could compose, paint, and write in serenity. He lived for two years in a cave with a family before having his own house built, totally adapting to their lifestyle. He speaks fluent Spanish, as well as German, English and French, and is working to master the language of the Tarahumara. One of the most amazing parts of the documentary was the tale of moving a concert grand piano that had been played by Anton Rubinstein at the opera house in Guadalajara to the very edge of the Copper Canyon. It got to Creel, the gateway to the Copper Canyon by train, I believe, and then the challenge began. Wheeler hired a truck and 18 men. He used two tons of potatoes as ballast on the truck to secure the piano. When the truck could go no further, the men took over, carrying the piano on their shoulders. The whole operation took 18 hours. The men were paid in potatoes.

The Tarahumara live a subsistence life, frequently going hungry, have no medical care and a child mortality rate of 50%; advanced education is unaffordable. Wheeler undertakes world-wide piano concert tours annually. The money he raises is used to meet some of these needs. He gives scholarships and buys food and medicines for the Indians. He has built a modern House of Healing and hired a nurse who provides care to 400 families. Wheeler dresses in the Tarahumara style, which includes a loincloth (he was wearing pants in SMA), special shirts, and sandals made out of tires. The Q&A probably lasted longer than the documentary as we just wouldn’t let this unique individual go. I asked if SMA was on his concert tour, and he said yes. I also asked if he had Internet access where he lives, and unbelievably, he does. He said it would be impossible to arrange his tours without it.

The following night, he played a concert in the biblioteca, which I attended. The room was packed. The piano was not the best in town (the best in town — a Steinway at St. Paul’s — was already in use at the time scheduled for the concert), but he rose above it. He plays like an angel. The man sitting next to me was sobbing. I recommend that you go to www.romaynewheeler.com and learn more about this unique man, and hear him play the piano. Try to hear him or someone else playing “Recuerdos de la Alhambra.” The way Romayne plays it sounds exactly like a guitar. I bought two copies of the documentary from him — as well as two CDs — but alas, there is something wrong with the DVDs and they freeze up. I am extremely disappointed as I want to share his story with as many people as I can.

I was having lunch with a friend from church and when she found out that I was here for six months this year and did not have a local doctor, she gently chastised me and told me to get a doctor forthwith! And I did! I had heard many recommendations for Dr. Roberto Maxwell, who had a Mexican mother and a gringo father. He speaks fluent English. Happily, his office is right around the corner from my apartment, so I went over and made an appointment and was able to see him the following day. He complimented my Spanish, although we spoke English when we were discussing my health, and also the very complete medical history that I keep and presented to him. He gave me his cell phone number, and said to feel free to use it at any time, night or day, when the office was not open. He typed much of my info into his computer and said that many doctors in town don’t keep records, but that he does. I feel much relieved to have taken this step.

El Dia de los Muertos – Part I

Talk about peak experiences! El Dia de los Muertos has to be at the top of my list. The festivities kicked off with a blow-out party at Fábrica la Aurora, Centro de Arte y Diseño, on Sat. night, Oct. 29, for the benefit of la Cruza Roja (the Red Cross). A bunch of folks who had helped out at Ojalá Niños’ Artwalk met first for pot-luck drinks and snacks and then walked together to the party, which was near the house we met in. At the entrance to this gigantic factory re-purposed as a collection of artists’ studios and galleries, we were met by a marimba band.

I loved to see the dads dancing with their little girls.

Not dancing, just looking incredibly cute!

Scary-looking things were around every corner.

This is a friend of mine — another Cynthia — from church.

Most of the artists had put up altars in their galleries or near-by halls and being artists, their creations were really something to see.

Not an altar, but a knock-out display anyway.

This one was striking due to the fact that it used no marigolds.

Don’t know who the deceased is, but check out the hammer and sickles surrounding the photo.

Because the place is so immense, there was room for other musical groups.

I went up to the jardin on Nov. 1, and was met by one of the most cheerful displays I’ve ever seen. There were pastel and then all-white papel picado strung across the vast expanse between the jardin and the parroquia, creating interesting shadows below.

And on the space underneath were submissions in a contest for students of the University of Leon (which has a campus in SMA) to create “carpets” made of seeds, rice, beans, and other natural materials like those found on the altars. One display was an homage to Steve Jobs (not this one).

Of course there were Catrinas of all stripes making the rounds. La Calavera Catrina (the Elegant Skull) is an icon of El Dia de los Muertos. They are (usually) humorous images depicted as skeletons, doing every possible thing you could think of. Where this woman is putting a donation is where the person in the costume looks out.

Vendors at the jardin had created their own altars to deceased loved ones, this an unusual two-sided one to honor both parents.

Not sure whose creation this is, since it’s right in front of the parroquia, but I really like it.

On Tues. evening, Nov. 1, I went to Camino Silvestre, a fabulous store where my daughter and son-in-law’s candles are sold, to see their altar to extinct Mexican birds, featuring the Imperial Woodpecker. (The owners’ original business was the manufacture and sale of glass hummingbird feeders, and now, in their store, in addition to dozens of models of the feeders, they have bird- and nature-related jewelry, pottery, notecards, candles, glassware, and on and on. Their in-store displays are extremely well done.) The owners had teamed up with the Audubon Society so that everyone who bought a membership or renewed got a free hummingbird feeder. The place was a madhouse! I could hardly get in the door, and people were spilling out onto the sidewalk. They had a musical group playing (seen to the left here), and were serving tiny tamales, atole (a hot corn drink that I don’t like), and white wine.

How cool that there were people looking in the window at the exact moment I took this shot. I never even saw them. Some of the hummingbird feeders can be seen in this photo.

I don’t know how I got this photo with no one in it!

Some guests at the party.

I returned to the jardin for some entertainment, and, as evening fell, the shadows that were created were splendid.

A group of youngsters, along with their teacher from La Casa de la Cultura, entertained the audience with a concert played on all-natural instruments. It was really quite amazing. It sounded just like a jungle, with bird noises, big cat sounds, drumming, a rain stick, etc.

I took many, many photos both with and without flash, to try to capture the parroquia, the lit cross on top, the papel picado, and the moon, and I got this one, which I’m very fond of because of the silvery cast to the church.

El Dia de los Muertos – Part II

I was totally unprepared for the intensity of emotions that greeted me on Wed., Nov. 2, when I went to El Pantheón Guadalupe, the municipal cemetery, for El Dia de los Muertos. Happily I was with three other people from the mattress-making group. There were police just to handle the foot traffic. The road to the cemetery was completely filled with vendors — mostly of flowers, but also of big, empty, restaurant-sized food cans that they’d saved to sell for either fetching water from the fountain or to put flowers in (the more enterprising folks even painted them), and food for the visitors.

As we neared the entrance to the cemetery, a waist-high rope was strung up in the street to separate those going in from those coming out. We were packed in the line to go in. I had to move my backpack to the front for safety.

And then we entered the cemetery and it was a riot of color, activity, music, food and drink, people of all ages. I was completely overwhelmed. Below is the first thing I saw when I entered the cemetery,

A typical chaotic scene.

In every aspect of life here, including in the cemetery, less is never more.

I think this is my favorite shot of the day. With his orange shirt and cap, matching the marigolds and the color of the tomb, it’s just about perfect. It says so much to me.

In addition to the gravestones, the niches — for the ashes of those who were cremated — were also decorated.

Someone in last week’s Atención suggested that since there usually are no flowers on the graves in the gringo part of the cemetery, it might be a nice idea to buy some on the way in and decorate those graves, also. Well, people took that to heart, and, while nowhere as festooned as the Mexican side, there were lots of flowers on all the graves, even the unmarked ones. Of course, we followed suit, and it was quite emotional to read the names and dates on the gravestones, and then to add a flower.

How restrained this gringo side looks! But peaceful for sure. We asked ourselves why there even was a gringo side, and decided that the separation was necessary because most of the gringos are not Catholic and the Mexican side is a Catholic cemetery, but there may be another reason.

I didn’t realize it until I got home and looked at the photos on the computer that I had taken a photo of the niche of George Bell, the 95 year-old friend of mine from the UU church here, who died just last June. I sent it to his widow, my dear friend, Peggy. One grave on this side featured a bag of M&Ms!

Members of Community Church set up a hospitality table on the gringo side, offering tequila, tamales, and a friendly presence. It’s the first year this has been done. I applaud them for it.

These are the people I came to the cemetery with.

Back to the Mexican side. People waited patiently for their turn to fill their buckets with water from a spigot at the fountain.

This is another favorite photo of mine.

If I’m here another year in the fall, I definitely want to go to the cemetery at night, as I hear there are thousands of candles burning and just a low murmuring sound as people talk quietly among themselves and perhaps to the deceased.

I have to wonder who, after the fiesta is over, removes the tons of flowers, candles, cans, etc. from the graveyard. It must provide plenty of employment for weeks.

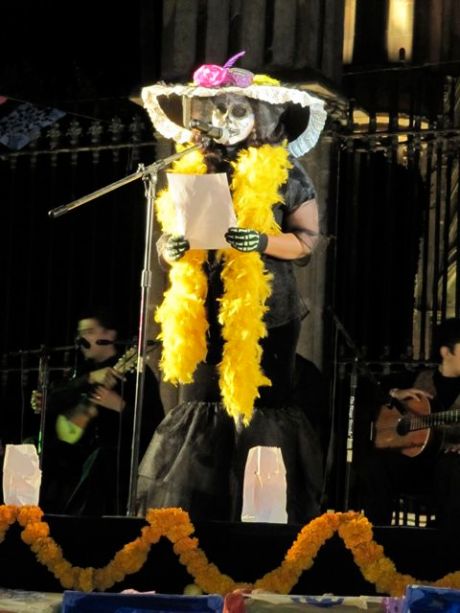

On the evening of El Dia de los Muertos, I again went to the jardin, where I witnessed a Catrina parade, and where there was a small orchestra playing, again, I think, from La Casa de la Cultura (just what they were playing, I honestly don’t remember at this point), the numbers interspersed with costumed folks reading works about death by famous Mexican poets, like Octavio Paz. The woman below is the director of La Casa de la Cultura.

On the Friday after the Big Day, when my flower lady came to the door, she had just two types of flowers for sale, when generally she has about a dozen. Her display looked pretty puny. When I asked her why there weren’t more flowers, she said they had all been used up for the fiesta (of El Dia de los Muertos).

And then on the 5th of November, the department store on the edge of town, La Luciérnaga, had El Encendido del Árbol Navideño, the lighting of the Christmas tree, kicking off the holiday shopping season. Sigh. You just can’t get away from it. I did not attend.

Someone Did Take Photos When we Played the Bells!

You’ll remember that I wrote that I took my camera to the service to have someone photograph us playing the bells, but then thought better of it as it might be a distraction. Well, someone, unbeknownst to me at least, did take photos, and I’ve gotten copies of them. So here we are in the room my UU congregation rents weekly from the Hotel de la Aldea. We players were all dressed in white on top, and black on the bottom, and we wear white gloves while playing the bells. You can see that my music stand is on top of three hymnals to accommodate my trifocals!

Liz, our leader, in the middle, is introducing one of the pieces we played.

A Trip to La Cañada de la Virgen – Not for the Faint of Heart!

Just a quick wrap-up on some Dia de los Muertos items. By reading Atención very carefully, as I always do, I found out two interesting things that I thought I’d share with you. You’ll remember that I told you that there is a “gringo side” in the municipal graveyard. (I’m sure there’s a lovelier name for it than that.) Turns out it’s privately owned by what’s called the 24-Hour Association. Mexican law calls for all dead bodies to be either buried or cremated within 24 hours. Older gringos who live in Mexico and care to, join the non-profit Association for about $500 USD per year, and fill out innumerable forms, and if they should die in Mexico, the Association swings into action, dealing with the embassy, getting death certificates, getting the body buried or cremated, informing next-of-kin, etc. What a valuable service for loved ones who may be in the States or Canada or elsewhere, are not familiar with Mexican law, probably don’t speak Spanish, and are, of course, also in grief.

The other thing was that perhaps in some of my photos of the “gringo side,” you saw Mexicans placing flowers on the gravestones or niches. Again I learned in Atención that some devoted former employees of deceased gringos come to offer a token. Because of the generosity of the Community Church of SMA, with their drinks and tamales that I told you about in the last e-mail, the Mexicans were able to hang around a bit, socialize, and be refreshed. I certainly hope that’s a custom that church will continue year after year.

Here’s another T-shirt story: There is a large, commercial bakery here (Wonder Bread-esque) called Bimbo. All of the bakery’s workers wear the shirts and they’re even sold in stores. I just always get a kick out of seeing a guy wearing a white shirt with bold red letters, saying “Bimbo.” Thank goodness they don’t know what it means in English.

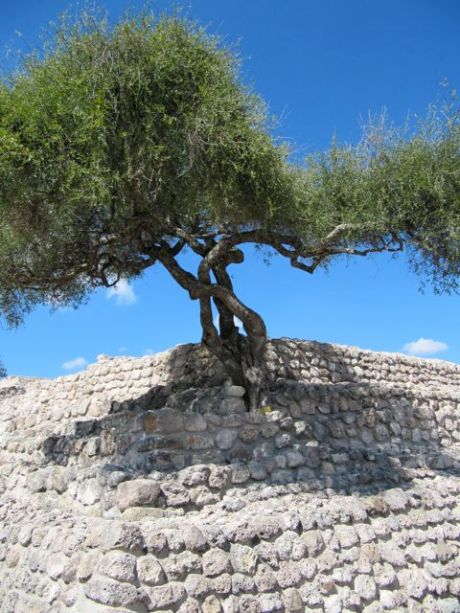

I had been wanting to visit the ancient pyramids, La Cañada de la Virgen (the “Canadian virgin,” as a Canadian friend and wag calls it), since it opened to the public last February. This Canadian friend went last March, when it was quite hot, and cautioned me to wait until the fall for my visit as it’s over four hours of strenuous walking and climbing in unrelenting sun. “Cañada” has nothing to do with the country of Canada (note that it’s an ñ, not an n). It means canyon. La virgen part comes from a geode that was found on the site with the image of the virgin, and miracles have been attributed to her.

Two friends from mattress-making and I signed up for a tour beginning at 9 a.m. with Albert Coffee, who is unique among the guides. Albert is an anthropologist and archeologist who worked on the project in excavation, mapping, and in the lab. He’s also a gringo, so speaks English. The guides at the site do not speak English, although I was pleased to see that interpretive signs along the way were in both languages. You cannot visit the pyramids without an official guide. We were to have a comida at a ranch nearby after the tour, but for some reason, that part got cancelled.

Albert picked us up, along with four others, from Montreal and Italy, in his van outside of Starbucks. I borrowed a wide-brimmed hat from my landlady, bought a bottle of water to supplement the one I always carry, and greased myself up well with sun block. As we drove the 15 minutes or so to the site, Albert started to fill us in on what we’d be seeing. He told us of the genius of the planting of the “three sisters” — corn, beans, and squash, and how the beans and corn, along with rice, form a complete protein. The beans grow up the support provided by the corn stalks, and both of these shade the squash planted below from the intense sun. He said that there may be hundreds – perhaps even thousands — of other small pyramids in the area. He pointed out a couple of un-excavated ones on our way. He said that the people around the site are still living as they did 200 years ago, except that instead of goat herders, there are cowboys with cell phones. When we passed the presa (dam), he said that the water level is the lowest he’d seen it in the 11 years he’s been in SMA, and it’s now just two months since the “rainy season.” They are just not getting the amount of rain that they used to. This year’s corn crop is stunted. One of the reasons I came in the fall was to experience the town in a different season. I was told that when I came in Sept., everything would be green and that flowers would bloom abundantly. NOT! Everything is dry and brown, just as it is when I come in the winter. Albert told us that we do not depend on the presa for our drinking water, but on an aquifer, which has only 10 years of life left in it. Somebody told me we were accessing 35,000 year old water in the aquifer because it’s not filling up anymore; we’re just pulling from it. Not a cheerful thought for this region.

The pyramid site is on the largest ex-hacienda in the country — 600 hectares (there are .404685642 hectares in an acre. You do the math; my eyes have glazed over) and is the largest piece of property left in the municipality. It is a work in progress. They wanted to get it open to the public as soon as feasible. There is much exploration yet to be done. The money to explore it so far has come from the Feds, state and local sources, including SMA hotel owners hoping to increase tourism. Newly-opened as it is, it already gets 5,000 visitors per month, the second highest of these sites in the country. Located in the central basin of the Laja River, the ceremonial center and elite burial ground are built on a very strategic plateau, since the site is surrounded by canyons and access is not easy. The site was occupied by an elite class of priests and rulers who observed the heavens and their movements as they related to an ancient agricultural/hunting and gathering calendar. It is also the final resting place for those inhabitants. “Given its geographic location, architectural design, and the sanctity of its natural landscape, Cañada de la Virgen was likely the regional center of power, where groups from a variety of cultural backgrounds co-existed.” (“Cañada de la Virgen: Refugio de los Muertos y los Ancestros,” by Gabriela Zepeda García Moreno, who incidentally was the lead archeologist on the project and the Mexican-speaking guide that day.)

Before any work could begin, there were five years of negotiations with the very eccentric German owner, Regina Thomas von Bohlen. She would put padlocks on gates across access roads to the site that had been paid for with state and municipal funds. She was constantly entering and leaving the country, making setting up meetings with her extremely difficult. Finally, the federal government had had enough and told her she could donate the land or have it seized by eminent domain. She chose the former, and in that way was able to put tons of restrictions on the deed. To this day, she has her own guards watching to see that these restrictions are adhered to. As we began our walk to the site, a teenager from the group with the Spanish-speaking tour-guide walked off the road, and Albert told us that if one of her guards had seen that, she could shut the whole operation down. The Mexican tour guide yelled at the kid and got him right back up on the road. It is a protected biological site. (Just as a side note, in this week’s Atención, the front-page headline says, “Cañada de la Virgen certified as Natural Protected Area,” and the article said that it was thanks to the initiative and efforts of Regina Thomas von Bohlen that it was possible to obtain the certification to support the conservation of this rich natural resource.

One parks at the visitor’s center (also a work in progress, but they did have bathrooms) and boards an official site bus which drives to within about 3/4 of a mile of the pyramids on cobblestone roads. From there it’s almost all up-hill walking and with no shade. The palapa (shack) in the distance in the photo below was it as far as shade went on the entire visit, and because the guides kept the groups apart and the Mexicans started out ahead of us, they got to it first.

First view of a pyramid. The four architectural complexes were constructed gradually over a period of 500 years from about 540 to 1050 AD in three distinct stages, as evidenced by the different materials used in each stage. Those who studied the pyramids estimate that the site was abandoned sometime between 1050 and 1100 A.D., probably because of drought. Interestingly, this is the same time period in the which the Anasazi vanished. You cannot believe the list of different specializations of people who worked on the excavation, some I’d never heard of and can barely pronounce, for example, archaeoastronomers and pedologists (soil science).

The 13-year excavation project cost between $2 and $3 million USD.

We were told that the wet stuff inside of cactus leaves was used as part of the mortar here, and of course the builders had to go farther and farther afield to get the nopales they needed as local supplies were decimated.

The re-constructed shards below were in a garden of sorts off to one side. Albert told us that many intact pottery pieces were also found. They are currently in safe storage awaiting their placement in the museum at the visitor center. On the way out, I bought a bi-lingual book about the pyramids and learned that frequently pottery was “killed” (purposefully shattered as part of a ritual) along with people when human sacrifice was practiced, including of newborns and children. There was also blood-letting as they believed that they had to put their own blood into the ground to keep the seasons turning. And then there were mutilation practices for the purpose of ritual cannibalistic communion, practiced only by the high priests and rulers.

Albert told us that you can sum up the lives of the builders of the pyramids in two words: ancestor worship. There are four complexes on the site, only three of which have been excavated. In Complex A, also known as La Casa de los trece cielos (the house of the 13 heavens), a burial site was found of a figure they named “El jerarca” (the hierarch), so named because he is believed to have been one of the most prominent forefathers of Cañada de la Virgen’s ruling caste, due to the antiquity of his bones. Another skeleton, called “La Niña Guerrera” (the girl warrior) was originally thought to be a boy. They are both 1000 years older than the other burials on the site. It is believed that these bones were kept in a “funerary bundle” or a “sacred bundle” and carried around for all of those years during their migration into this region. There were a total of 19 burials unearthed on the site. It was believed that these could have been the collective sacrifice and interment of a defeated family lineage that once embodied the ruling caste. All burials took place along with a dog, usually a chihuahua, as a guide into the darkness of the underworld. When they unearthed the skeletons, there was always a dog’s skeleton held to the deceased’s chest. They also ate chihuahuas.

Complex B, the House of the Longest Night, associated with the winter solstice, had a sweat lodge. Complex D is La Casa del Viento (the house of the wind, and would you believe it, as soon as we neared it, we could feel the winds picking up). Complex C has not yet been excavated, as well as several housing complexes.

This is the horse of one of the guides. Those men who worked the hardest and longest on the excavation project were rewarded with jobs as guards, and they use horses to commute to work.

“All of the complexes are aligned to many important events that occur in the sky over the course of the year. They precisely monitor the movements of the sun, moon,Venus and Jupiter as they mark seasonal extremes and important dates in the ancient Otomí-Mexica calendar. The structures also imitate the forms of the surrounding hills and mountains, displaying the mind-boggling amount of genius involved in the planning and building of a place that incorporates both the cosmos and the landscape into its architecture.” (Atención)

You can see from this shot of one of the interpretive signs that the moon is lined up perfectly at the top of the pyramid. The book I purchased laid out in much more detail all of the measurements they made which produced sun rises and sunsets and moon rises and other astronomical events to line up with parts of the pyramid.

The most prevalent theory about the sunken patios is that they were flooded with water to allow the people to study the stars without having to look up. Others said the flooding theory couldn’t be correct as the fairly stiff breezes there would create ripples. We were thrilled with those breezes, which blew constantly and made everything much more pleasant. I didn’t sweat and I didn’t need all of the extra water I had brought.

The sunken patios were also used as a collection point for rainwater during the rainy season, then channelled by means of a canal which met up with those from the other patios, into the nearby pond, Amanalli, which was used as a reservoir. Albert said it provided the people of that time with sufficient water until the next rainy season. The existence of this reservoir was an important factor in the decision to choose this area to build the pre-Hispanic settlement. Interestingly, on the front cover of the book I bought is a magnificent photo of the Amanalli, filled with water reflecting a blue, cloud-filled sky with a pyramid in the background. And many photos inside the book show a green, lush countryside. Those photos must have been taken within the 13-year period of excavation, so not that long ago. Today, there is not a drop of water in the area where that reservoir was.

Another interesting thing to me was that after all of these years of work by dozens of different experts, it is not known with certainty who built the pyramids. One theory states that the first settlers of the ceremonial center were of Otomí descent. Others believe that there is a link between the inhabitants of Cañada de la Virgen and those of Zapotec villages in Oaxaca. For now, though, research will focus on the Otomí culture.

This tree is being allowed to grow where it is. They found out by bitter experience that the roots of these trees are holding everything together underneath.

Here we go up the many, many steps, which are narrow and steep. And of course there are no railings or ropes or anything really to hold onto. Most of us went to one side or the other and climbed in a stooped position, holding onto the rocks you see here. There was one problem, however. One of the rocks I held onto for balance and stability on my way down came right off in my hand! Albert said that after the first person falls down the stairs, the government will surely close down stair access to the top.

You can see the number of steps we climbed. The next morning, my knees, legs, and particularly my butt were so sore I could hardly walk or sit down in a chair or get up. For three days I suffered. I guess my muscles were not accustomed to being used in that way.

I learned a new word: syncretism, the amalgamation or attempted amalgamation of different religions, cultures, or schools of thought. Catholicism had a relatively easy time taking over or melding with the existing religion, because of the practice of blood-letting (compare to the host being “the blood of Christ”), the cross already existing as a symbol (the sub-structure of the pyramids was in the shape of a cross and served a public ritual purpose), and processions (which were already an integral part of their rituals).

You can see that I was enchanted by this trip, and am now eagerly reading more about the site.

Another three-Ring Circus

Last weekend was the celebration of the Revolution of 1910, not to be confused with the War for Independence from Spain, exactly 100 years earlier. I caught only the very tail-end of the celebratory parade on Sunday.

Starting before that celebration and lasting for at least a week after it is the Feria de la Lana y el Latón, a wool and brass market, although most of the metal I saw was tin. There must be at least 100 of the tiny booths. The woven wool rugs from Oaxaca are exquisite, and there are also wool caps, scarves, mittens, shawls, etc., in preparation for the winter months ahead, although it’s been a remarkably warm November.

The metal objects are varied and fun, with an emphasis on Christmas decorations — trees, angels, stars. The day after Thanksgiving, the Christmas decorations started to go up around town. I guess I should feel lucky that it wasn’t before that.

A bakery I’m familiar with somehow sneaked into the mix. They had an oven set up right there in the street and a baker was rolling out treats as fast as he could. Business was brisk. I admit to buying one of their large, delicious granola cookies.

And, of course, at the same time that all of this was going on, the five-day 9th Annual Jazz & Blues Festival of SMA was in full force. The opening night was free and outside in the jardin on a lovely evening, and featured a local group, the Vudu Chile Blues band, which was excellent. I discovered that I really, really like the blues. I thought it was a super idea to have the first night’s concert be free to all, to whet appetites for more.

This group, starring Pedro Cartas with Zambé, was not part of the jazz festival, but they do play jazz every Thursday, Friday and Saturday nights at a favorite restaurant of mine, Hecho en México. A few friends and I got a reservation and had a lovely dinner and a grand time listening to this violin virtuoso and his cohorts. You can hear them on You Tube. Just search for “Pedro Cartas y Zambé en restaurante Hecho en México en México SMA.” Stay tuned for the whole piece, as the real violin fireworks happen near the end. I will definitely go to another one of their sessions when I return in the winter, and I’d love to get a CD.

There were many other concerts, including a Stan Getz tribute, and for the grand finale, a Stevie Wonder tribute, which I attended. Here are the San Miguel Jazz Cats doing their thing to honor Stevie. The man on the left, all dressed in black, Rich Singer, was the most incredible harmonica player I’ve ever heard. He had a little suitcase of different harmonicas. I never knew there was such a thing; I thought they were all alike.

I was invited to a friend’s birthday party on her lovely patio late on a Sunday afternoon.

She even had a gypsy guitarist, Javier Estrada, to entertain us. His playing is not to be believed. I have never seen fingers move that fast, plus he strikes the wood of the guitar with his hand, and I find his playing very exciting.

Every Sat. morning, I meet a group of women from my UU congregation for breakfast at Mama Mia’s. And every Sat. morning, an artist/salesman of beautifully decorated clay animals comes to the table to try to sell us his wares. Most restaurants in San Miguel allow this activity. Several of the women in the group have bought many pieces from him. This time, he had a huge snake, which my friend, Alicia, below (she’s the one who had the birthday party) was interested in. Here, the artist was offering a mask, which was made from wood.

Here they’re bargaining. The price didn’t get down far enough for Alicia to buy the snake. But we all enjoy this guy and his schtick. He’s got turtles, chihuahuas, pigs, you name it.

I was privileged to attend not one, not two, but three different Thanksgiving feasts. The first one was a luncheon for the benefit of Mujeres en Cambio, a favorite charity of mine here, two weeks before the big day. We had a complete Thanksgiving meal that was delicious. Then on the Wednesday before turkey day, I was invited to join Nancy, a woman from Seattle whom I met at the Writers’ Conference here last Feb., her husband, Dwayne, and their son, Tad, who were in town for the Jazz & Blues Festival, to join them for their pre-Thanksgiving feast. What a meal that was, so imaginative, with their special takes on traditional Thanksgiving fare, such as chipotle mashed sweet potatoes. It was a marvelous meal and grand to be with their family. Their rental was in a part of town I’d never explored, so that was enlightening.

Here is the sunset from their rental which is way, way, way up on one of the hills in town.